Two CEOs Could Start the AI Treaty We Need: Why Aguirre's Assurance Contract Proposal is Revolutionary

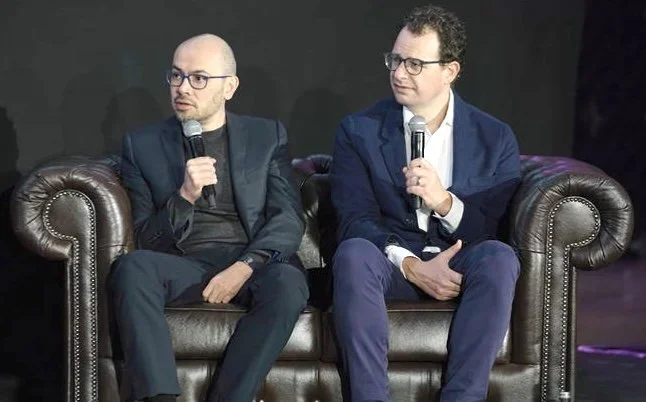

Hassabis and Amodei, in a February 2025, in their first joint interview with the Economist’s editor-in-chief, that preceded the recent one at the WEF 2026.

ABSTRACT: At Davos 2026, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei admitted he'd prefer to slow down the AI race—but can't, because "we have geopolitical adversaries building the same technology at a similar pace." Then came the crucial revelation: "This is a question between me and Demis [Hassabis]—which I am very confident we can work out."

Anthony Aguirre of the Future of Life Institute responded proposing on X a mechanism that could let them do exactly that: an assurance contract where labs commit to slowdown terms that activate only when enough others sign. No one moves first. Everyone moves together.

This post analyzes why this configuration is revolutionary, profiles other AI leaders most likely to join (Altman, Suleyman, Musk, Sutskever), and explains what such an agreement could and should trigger: not just a pause, but a proper US-China-led global AI treaty. We discuss hos such assurance contract should contain a call for Xi and Trumop to engage in a global AI treaty, specifying minimum requirements for such treaty-making process to ensure it with reliably and durable prevent the safety risks and reduce global concentration of power and wealth.

(this Abstract is followed by a 800 words post and an optional 3500 words blog extension)

At the World Economic Forum's "Day After AGI" panel in Davos, the CEOs of the world's two most safety-focused AI labs made a striking admission. Dario Amodei of Anthropic, who predicts AGI within 1-2 years, said he'd prefer Demis Hassabis's more cautious 5-10 year timeline: "I wish we had 5 to 10 years... Why can't we slow down to Demis' timeline?"

His answer was revealing: "The reason we can't do that is because we have geopolitical adversaries building the same technology at a similar pace. It's very hard to have an enforceable agreement where they slow down and we slow down." But then: "If we can just not sell the chips [to China], then this isn't a question of competition between the U.S. and China. This is a question between me and Demis—which I am very confident we can work out." To which Hassabis nodded.

They’ve made more clear what they hinted in the past: the two leading safety-focused AI labs could coordinate a slowdown between themselves—if only the other labs and the US-China race weren't forcing their hand.

Aguirre’s Proposal

Anthony Aguirre, executive director of the Future of Life Institute, responded to such statement on X with a proposal mechanism that could let them do exactly that—an assurance contract: they sign a formal, binding, detailed conditional commitment to pause all potentially catastrophic AI activities. The agreement is conditional, i.e. it becomes binding only when and if a sufficient number of other top US and Chinese labs do so. As Aguirre clearly and succinctly stated on his post on X:

From the "Day After AGI" event in Davos:

Zanny Minton Beddoes: You could just slow down.

Dario Amodei: [...] we can't do that [...] because we have geopolitical adversaries building the same technology at a similar pace. It's very hard to have an enforcable agreement where they slow down and we slow down.[...] if we can just not sell the chips, then this isn't a question of competition between the US and China. This is a question of competition between me and Demis, which I'm very confident that we can work out.

@DarioAmodei and @demishassabis : you can do it in the opposite order. As you both know, there is a game-theoretic solution to the problem of "we'd slow down but there's no coordination," which is an assurance contract. In particular, you could:

1. Get together and agree on what sort of slowdown you'd like – for example a cap on the total FLOP and FLOP/s (see http://ktfh.ai appendices for concrete proposal) pending strong scientific consensus that controllability and other issues have real solutions. Include compute-based and other mutual verification mechanisms. The agreement should still allow lots development of awesome controllable AI tools, just not high-level autonomous AGI and superintelligence. You guys are super competent and reasonable. You could do it.

2. Agree on who else would need to sign that agreement for you to feel comfortable enacting it. Include non-US companies.

3. Sign said agreement, which only goes into effect if all (or N of M) of the parties in step 2 sign also.

4. Encourage/pressure the additional AGI efforts to sign as well. Once you get going you might be surprised at who signs. In the meantime, no competitive advantage is lost.

5. You don't actually need to get everyone. Once there is critical mass on a concrete proposal, strong pressure can be put on the USG to (a) turn this into executive action enforced domestically by the USG and many places via the compute supply chain; (b) work out something with China for them to enforce the same domestically and in their sphere of influence. The PRC government does not want to lose control of or to superintelligence either. The chip supply chain can be a powerful mechanism here as well.

Any level of partial success here would still be a game-changer.I think you both fully understand that we're in a worst-case scenario as envisaged when you started in this years ago: the all-out race with zero cooperation is most likely to get us some mix of war, large-scale accident, gradual disempowerment, and uncontrolled existentially-risky singularity. This is one of the very few offramps remaining, and probably the best.

FLI would be more than happy to support in any of these steps, in any way we can, as neutral facilitator or otherwise.

The configuration proposed by Aguirre is revolutionary because it resolves the coordination problem Amodei described. No lab has to move first in the hopeless hope that others will follow. All commit simultaneously—but only once enough others have committed.

Who Are Amodei and Hassabis?

These aren't minor figures. After Trump and Xi, they are among the 3-4 most powerful people, beyond Trump and Xi, whose actions will decide whether humanity thrives, suffers, or survives the AI transition.

Dario Amodei left OpenAI in 2021 over safety disagreements. He has stated that solving AI alignment without governance would "by definition, create an immense undemocratic concentration of power." His Davos statement wasn't a departure—it was a restatement of views he's held for years.

(See Strategic Memo v2.6, pp. 221-244)

Demis Hassabis, Nobel Laureate and Google DeepMind CEO, has been the most vocal AI leader on governance. He's called for a "technical UN" for AI, stated that governance should be "something like the UN," and concluded, "As we get closer to AGI, we've probably got to cooperate more, ideally internationally."

(See Strategic Memo v2.6, pp. 245-250)

Why Other Top AI CEOs Would Likely Join

If Amodei and Hassabis moved first, other lab US AI leaders would not only face significant pressure but, most significantly, most of them would very welcome the initiative given their previous statements:

Sam Altman (OpenAI) has already called for a "Constitutional Convention-style assembly" and stated the US "should try really hard" for an agreement with China. Call even in October 2025 for an IAEA for AI. His pivot to racing was a probability reassessment, not a philosophical conversion. (pp. 183-200)

Mustafa Suleyman (Microsoft AI) has defined existential red lines and positioned Microsoft as a "willing early follower." (pp. 216-219)

Elon Musk (xAI) remains a wildcard but has repeatedly called for nuclear-level AI regulation while racing—an assurance contract gives him a credible mechanism to pause without unilateral sacrifice. (pp. 301-313)

The Real Revelation

The success of this setup demonstrates an important fact: the leaders of AI labs do not want the current acceleration. Despite posing as the industry's representative, Trump's current accelerationist AI policy only represents a small portion of the accelerationist, post-humanist camp, which is outside the AI industry (Thiel and Sacks). Global governance is something that the leaders who are actually developing frontier AI have called for time and again.

An assurance contract wouldn't just pause the race—it would realign the political map around a position most stakeholders already hold but haven't had a mechanism to coordinate on. 77% of US voters support a strong international AI treaty. The mechanism exists. The philosophical alignment exists. What remains is the decision to act.

The Obstacles—And Why They're Surmountable

Can Hassabis and Amodei actually sign such a commitment given their corporate constraints? Would China engage? How would anyone verify compliance? These are serious questions—but each has answers. An assurance contract is conditional, minimizing corporate risk until activation.

China has consistently signaled openness to AI governance, from Xi's Global AI Governance Initiative to Vice-Premier He Lifeng's Davos 2026 warning against "two different systems." And verification—the hardest problem—requires the unique expertise of superpowers' security agencies working together to build mutually-trusted systems. (See Extended Case for details)

Beyond the Spark: What the Assurance Contract Would Trigger

Aguirre's proposal is brilliant—but insufficient alone. By itself, it would slow the race by months at best. It lacks the capabilities, expertise, and legitimacy to enforce commitments durably and globally. What makes it transformative is what it would trigger: if handled well, it could become the starting pistol for the proper, extraordinarily bold, US-China-led AI treaty we desperately need.

This could enable other key potential influencers of Trump's AI policy, including Vance, Bannon, Rogan, Carlson (and more) to join in to attempt to sway Trump’s towards co-leading with Xi a proper AI treaty, as suggested by the Coalition for a Baruch Plan for AI’s The Deal of the Century Initiative, led by this author. That requires a treaty-making process with real teeth, enforcement mechanisms built on defense-grade technology, and safeguards against concentration of power.

What the Agreement Should Demand

The conditional agreement cannot simply be a pause commitment—it must be a call to action addressed to Trump and Xi. It should specify that the pause is temporary and conditional on governmental action: a formal treaty-making process with minimum characteristics including time-bound negotiations, formal lab participation, democratic legitimacy, anti-authoritarian safeguards, and periodic reconstituent processes that prevent permanent lock-in. By embedding these requirements, Amodei and Hassabis wouldn't merely pause the race—they'd be helping substantially increase the probabilities that a global AI treaty will produce positive outcomes.

Extended Blog Post Case (~3,200 words)

The Men Who Could Change Everything

Together with 3-4 other leaders and financial leaders that control US to AI labs, Dario Amodei and Demis Hassabis are, after Trump and Xi, arguably among the most powerful people deciding whether humanity thrives, suffers, or survives the AI transition.

They lead the two labs—Anthropic and Google DeepMind—that nowadays’s most focused on AI safety and global governance while remaining at the frontier of capabilities. Their decisions in the coming months may matter more than those of any elected officials.

Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, left OpenAI in 2021 explicitly over safety disagreements. He has been remarkably candid about risks. In a 2023 interview, he stated that solving technical AI alignment without solving governance would "by definition, create an immense undemocratic concentration of power." He proposed that any entity at the forefront of AGI should "widen that body to a whole bunch of different people from around the world. Or maybe... some broad committee somewhere that manages all the AGIs of all the companies on behalf of anyone."

His Davos statement wasn't a departure—it was a restatement of the dilemma he's articulated for years: labs cannot unilaterally slow down without risking that less safety-focused competitors win the race. (See Strategic Memo v2.6, pp. 221-244 for full Amodei profile)

Demis Hassabis, CEO of Google DeepMind and 2024 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry for AlphaFold, has been the most vocal supporter among AI leaders of strong global governance. His calls have grown more specific over time:

He called for a "technical UN" for AI safety—combining elements of CERN, IAEA, and a governance body

In a joint Economist podcast with Amodei, he stated that "ideally it would be something like the UN" for AI governance—remarkable from a sitting AI lab CEO

He called for non-superpower nations—UK, France, Canada, Switzerland—to form a coalition advancing global AI regulation

In February 2024, when confronted about Google controlling transformative AGI, he concluded, "As we get closer to AGI, we've probably got to cooperate more, ideally internationally."

In July 2023, Google DeepMind published Exploring Institutions for Global AI Governance—the most detailed governance framework from any major AI lab, proposing four new international governmental organizations including a "Frontier AI Collaborative."

These are not extemporaneous statements at Davos. They represent years of consistent positioning by both leaders—positions their companies' competitive pressures have prevented them from acting upon. (See Strategic Memo v2.6, pp. 245-250 for full Hassabis/Google profile)

The Proposal That Could Break the Deadlock

Aguirre proposed a classic game-theoretic assurance contract—but with a crucial twist that addresses exactly the dilemma Amodei articulated:

From the "Day After AGI" event in Davos:

— Anthony Aguirre (@AnthonyNAguirre) January 22, 2026

Zanny Minton Beddoes: You could just slow down.

Dario Amodei: [...] we can't do that [...] because we have geopolitical adversaries building the same technology at a similar pace. It's very hard to have an enforcable agreement where they…

The configuration is revolutionary because it resolves the coordination problem Amodei described. No lab moves first. All commit simultaneously—but only once enough others have committed. The race doesn't pause for unilateral sacrifice; it pauses for mutual agreement.

The conditional commitment: Amodei and Hassabis specify concrete terms—perhaps FLOP caps pending scientific consensus on controllability or mandatory safety evaluations before capability jumps. These become binding only when activation conditions are met.

The activation threshold: When a certain high percentage (say 80%) of top AI labs (by compute capacity or capability level) sign, all signatories commit to jointly call upon governments worldwide to enforce compliance on holdouts and to begin formal treaty negotiations.

The cascade effect: Once Anthropic and Google DeepMind signal willingness to pause under specific conditions, the political economy shifts. Other labs face a choice: join the emerging consensus or be branded as reckless actors willing to gamble humanity's future for competitive advantage.

As Aguirre noted: "You don't actually need to get everyone. Once there is critical mass on a concrete proposal, strong pressure can be put on the USG." The assurance contract creates that critical mass.

Why Other AI Leaders Would Likely Join

If Amodei and Hassabis moved first with a conditional commitment, other major AI leaders would face intense pressure—and many would have strong reasons to join. In fact, a number of them appear very inclined to finding a way to slow the ongoing mad race and promote strong global governance of AI. Our analysis in Strategic Memo v2.6 profiles each in depth:

Sam Altman (OpenAI)

Altman is perhaps the most persuadable major AI figure despite his current racing posture. He has already articulated the exact governance vision the coalition would need—calling for a "Constitutional Convention-style assembly" for AI governance and publicly stating the US "should try really hard" for an agreement with China.

His pivot to racing rhetoric was a probability reassessment, not a philosophical conversion. Faced with governmental inaction and immense commercial/geopolitical pressure, he concluded racing was the least-bad option. An assurance contract changes that calculus—if other major labs commit conditionally, OpenAI no longer faces the choice between unilateral pause (suicide) and racing (gambling humanity). (pp. 183-200)

Mustafa Suleyman (Microsoft AI)

Suleyman has done something no other major AI lab leader has: publicly defined red lines he considers existential. In his November 2025 announcement of Microsoft's "Humanist Superintelligence" team, he articulated four capability thresholds: AI that can "recursively self-improve, set its own goals, acquire its own resources, and act autonomously."

He has stated publicly that "only biological beings can be conscious"—creating unexpected common ground with Christian humanists. He called out Meta's and OpenAI's pursuit of "ill-defined and ethereal superintelligence" as philosophically bankrupt.

Microsoft has positioned itself as a "willing early follower" rather than accelerationist leader. If Anthropic and Google signal openness, Suleyman could become the first major voice to publicly endorse treaty-making. (pp. 42-43)

Elon Musk (xAI)

Musk presents the most complex case. His "too late to regulate" pivot in October 2024 represented a probability reassessment that could harden further—or reverse.

But several factors suggest openness:

He was first warned about AI risks by Hassabis himself in 2012—reportedly pausing "almost a minute" processing, then investing $5M in DeepMind

He has repeatedly called for years for global AI regulation comparable to nuclear controls, even while racing

His stated belief that the UN should be abolished may mean he seeks a better global institution, not none

He half-joked about "wanting to be alive to watch AI armageddon happen, if it must happen, but hopefully not cause it"

A conditional assurance contract gives Musk something he's never had: a credible mechanism to pause without unilateral sacrifice. Whether he'd join is uncertain—but dismissing the possibility would be premature. (pp. 301-325)

Ilya Sutskever (SSI)

Sutskever's departure from OpenAI and subsequent focus on "safe superintelligence" signals appetite for principled positions. He recently told Dwarkesh Patel that it would be "materially helpful if the power of the most powerful superintelligence was somehow capped," advocating for "some kind of agreement or something" for extremely powerful AIs. (p. 71)

The Real Revelation: It's Not the Companies Driving the Race

This potential configuration reveals something crucial: the current acceleration isn't what AI lab leaders actually want.

Trump's AI policy reflects the agenda of a narrow faction—the accelerationist, post-humanist camp led by Peter Thiel, with investors like Marc Andreessen playing along. But the leaders of the companies actually building frontier AI—Amodei, Hassabis, Altman, and Suleyman—have repeatedly called for exactly the kind of global governance the assurance contract would catalyze.

If these leaders went to Trump with a conditional commitment, they would demonstrate that:

The companies themselves favor coordination over racing

American economic interests and leadership are better served by a US-China treaty than a winner-take-all gamble

Trump's current advisors have steered him toward a position that neither the public nor the industry actually wants

The political coalition waiting to form is larger than it appears. 77% of US voters support a strong international AI treaty. 63% believe it's likely humans won't be able to control AI anymore. Steve Bannon has called for the AI race to be "stopped." Pope Leo XIV has repeatedly warned about AI risks. Tucker Carlson has expressed alarm. JD Vance has called for the Pope to lead on framing AI ethics.

An assurance contract initiated by Amodei and Hassabis wouldn't just pause the race—it would realign the political map around a position most stakeholders already hold but haven't had a mechanism to coordinate on.

The Obstacles—And Why They're Surmountable

Corporate Governance and Investor Pressure

Hassabis works for Larry Page and Sergey Brin, whose post-humanist philosophies diverge sharply from his governance vision. Amodei faces board dynamics and investor expectations. Neither can act unilaterally.

But an assurance contract is conditional—it only activates when others join. The corporate risk of signing is minimal until activation, while the reputational risk of not signing—once the mechanism exists—could prove substantial.

China's Position

Would China join? As we've documented, China has consistently signaled openness to AI governance—from Xi's Global AI Governance Initiative to Vice-Premier Ding Xuexiang's warning at Davos 2025 that chaotic AI competition could become a "grey rhino"—a visible but ignored catastrophe. At Davos 2026, Vice-Premier He Lifeng reiterated China's commitment to Xi's Global Governance Initiative and warned that the world falling into "two different systems" would have "unimaginable" consequences, calling on nations to "resolutely oppose Cold War mentality and zero-sum games." A lab-initiated assurance contract doesn't require China upfront—it creates momentum that makes governmental negotiation possible.

Verification Challenges—And Why Superpowers Hold the Key

How would labs verify each other's compliance with FLOP caps or safety protocols? This is genuinely difficult—but the solution lies not primarily in academic research or NGO proposals, but in the unique expertise of superpowers' security agencies.

As we detail in Strategic Memo v2.6 (pp. 133-142), US and Chinese security agencies possess adversarial hacking expertise that academics simply lack. They know how sophisticated actors circumvent controls, how to detect concealed programs, and how to verify compliance without revealing methods. Like the 1946 Acheson-Lilienthal Report that designed nuclear enforcement mechanisms, this treaty requires the highest defense-grade AI and IT security experts—not just diplomats and researchers—to architect enforcement. But this time, the Oppenheimers of our era must be in the same room for weeks with their Chinese counterparts.

The treaty-making process must mandate the joint creation of mutually-trusted control systems—built collaboratively by engineers from signatory nations on a foundation of battle-tested, globally-trusted, open-source technology. Critical systems will be mutually-trusted precisely because they are jointly-developed throughout the entire critical life-cycle, with cryptographically-enforced multi-jurisdiction oversight. Technologies like zero-knowledge proofs can enable nations to demonstrate compliance with compute limits without revealing sensitive details; blockchain-based audit trails can create tamper-proof records accessible to international auditors while protecting proprietary information.

Crucially, there are substantial overlaps between the technologies required for treaty enforcement and those needed for ultra-high-bandwidth, mutually-trusted diplomatic infrastructure—the kind of secure communication systems that would enable the spontaneous, high-frequency, leak-proof negotiations that a fast-moving treaty process demands. As the November 2025 Witkoff-Ushakov transcript leaks demonstrated, current diplomatic communications are dangerously vulnerable. Our proposal includes rapidly deployable, mutually-trusted containerized SCIFs (Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities), made to also support reliably-ephemeral remote communications, manufactured under joint US-China-neutral oversight, that would enable presidents and hundreds of staff to negotiate with Pentagon-level security from anywhere in the world, holding both formal and “hallway” and “trust building” informal talks.

If both the enforcement infrastructure and the diplomatic infrastructure are developed in coordination—as parallel workstreams of the same program—the synergies would significantly shorten timeframes. The same cryptographic foundations, the same jointly-verified hardware, and the same trust-building processes would serve both purposes. This is not a decades-long project; with sufficient political will and resources comparable to wartime mobilization, initial operational deployment could be achieved within months. (See Strategic Memo v2.6, pp. 115-120 on "Ultra-High-Bandwidth Treaty Negotiations" and pp. 133-142 on "Key Role of Superpowers' Security Agencies and Top AI Labs")

What Would Need to Follow

Aguirre's assurance contract proposal—while brilliant and crucial for AI governance—would not solve it at all and, just by itself, would slow the race down by a few months at best.

That is because it would lack the capabilities, expertise, and legitimacy to reliably and durably enforce commitments globally. It would also lack other important global governance functions that are needed—such as the prevention of immense concentration of power in some public or private entity, democratic accountability mechanisms, and much more.

What is incredibly promising is instead what it would most likely trigger.

If uptaken by Hassabis and Amodei—and handled well in its communications and timing with superpowers—it would have a good chance of becoming the spark, the starting pistol, the trigger of the proper, extraordinarily bold and timely US-China-led AI treaty that we desperately need.

A treaty-making process with real teeth: Moving from lab commitments to governmental negotiations requires diplomatic infrastructure that only nation-states can provide. The Realist Constitutional Convention model that we propose—weighted by GDP, time-bound, with supermajority rules—offers a viable template that avoids both the paralysis of UN-style consensus requirements and the illegitimacy of great-power diktat. Such a process would need to move at wartime pace, with dedicated diplomatic bandwidth comparable to the Manhattan Project's organizational intensity.

Enforcement mechanisms that actually work: Voluntary lab commitments, even coordinated ones, cannot survive sustained competitive pressure without governmental backing. The treaty must include enforcement mechanisms capable of detecting violations, imposing meaningful consequences, and—crucially—preventing both uncontrolled ASI and authoritarian capture. This requires what we call "trustless" verification systems: state-of-the-art cryptographic technologies and governance protocols that enable transparency without creating a global surveillance apparatus. The arXiv paper on AI Safety Treaties details technical approaches including compute monitoring, hardware-level controls, and staged verification.

Addressing concentration of power: As Holden Karnofsky has warned, the cure could be worse than the disease if governance concentrates power in unaccountable hands. Any treaty architecture must embed radical federalism and subsidiarity—ensuring power remains at the lowest possible level while still enabling effective coordination. This means formal roles for AI labs, civil society, and democratic institutions—not just governments. It means sunset clauses, rotation mechanisms, and distributed veto powers that prevent any single actor from capturing the system.

Preserving innovation and legitimate aspirations: A treaty that simply halts all AI development would fail politically and might even be counterproductive. The framework must distinguish between dangerous capabilities (recursive self-improvement, autonomous resource acquisition) and beneficial applications (medicine, climate, scientific research). It must create pathways for controlled experimentation and preserve space for the legitimate transhumanist aspirations that motivate some key players—while ensuring these don't come at the cost of human survival or freedom.

(For full analysis, see Strategic Memo v2.6, pp. 103-142 on treaty design and enforcement)

What the Conditional Agreement Should Also Call For

If Amodei and Hassabis are to sign an assurance contract that has any chance of catalyzing real change, it cannot simply be a pause commitment. It must be a call to action—explicitly addressed to the heads of state of the United States and China—to co-lead the treaty-making process that the labs cannot create on their own.

The conditional agreement should therefore contain, alongside specific slowdown terms (FLOP caps, safety evaluations, etc.), an explicit statement that the pause is temporary and conditional on governmental action. It should declare that signatories commit to these constraints only for a defined period—say, 18-24 months—during which the US and China must initiate a formal treaty-making process. If governments fail to act within that window, the commitment lapses—making clear that the burden of action lies with political leaders, not just lab executives.

More specifically, the agreement should call on President Trump and President Xi to jointly convene a treaty-making process with minimum characteristics necessary for a positive outcome:

Time-bound and ultra-high-bandwidth: A Realist Constitutional Convention-style assembly with a defined endpoint (perhaps 6-12 months), extreme dedicated diplomatic resources, an ultra-high-bandwidth mutually-trusted diplomatic communications infrastructure, and decision rules that enable progress without requiring unanimous consent. This is not another decades-long UN negotiation—it's a focused sprint with clear deliverables.

Technically informed: Formal participation by AI labs and safety researchers, ensuring that governance mechanisms are grounded in technical reality rather than political theater. The labs signing the assurance contract would commit to supporting this process with their expertise.

Democratically legitimate: Weighted representation that reflects both economic power and population, with mechanisms for civil society input and democratic accountability. The goal is governance that commands genuine legitimacy, not a great-power carve-up that breeds resentment and evasion.

Designed to prevent both catastrophic risks: The treaty must address Thiel's "AI Trilemma"—preventing both uncontrolled ASI (the "Armageddon" risk) and authoritarian capture (the "Antichrist" risk). This requires explicit anti-concentration provisions, distributed enforcement, and sunset mechanisms that prevent any permanent lock-in of power.

Adaptable and non-permanent: Perhaps most critically, the treaty must avoid locking in any particular set of values or institutional arrangements forever. Humanity's understanding of AI, its risks, and its potential will evolve—and governance must evolve with it. This means mandating periodic reconstituent processes for treaty institutions (perhaps every 10-15 years), ensuring that future generations can revise, reform, or even dissolve arrangements that no longer serve humanity's interests. It also means explicitly leaving open the possibility that, at some future point—when alignment science matures, when verification technologies improve, when humanity collectively chooses—we may decide to eventually develop ASI if an informed supermajority of humanity decides so. The treaty should be a pause and a framework for deliberation, not a permanent prohibition. Locking in today's fears as tomorrow's constraints for immense flourishment of humanity and sentient beings would be as dangerous as locking in today's recklessness.

By embedding these requirements in the conditional agreement itself, Amodei and Hassabis would not merely be pausing the race—they would be defining the terms of the peace. They would be telling Trump and Xi, "We've done our part. Now do yours. Here's what success looks like."

(For detailed treaty-making roadmap and enforcement architecture, see Strategic Memo v2.6: "Treaty-Making Roadmap" pp. 103-120, "A Treaty Enforcement that Prevents both ASI and Authoritarianism" pp. 121-142, and "The Global Oligarchic Autocracy Risk—And How It Can Be Avoided" pp. 143-158)

The Bottom Line

Anthony Aguirre didn't just float an interesting idea at Davos. He articulated a coordination mechanism that addresses the exact dilemma AI lab leaders have described for years.

The question now is whether Amodei and Hassabis—two leaders whose stated convictions align with exactly this kind of initiative—will act on their beliefs. Their public statements, spanning years, suggest they understand what's at stake. Their corporate positions have prevented unilateral action. An assurance contract removes that constraint.

History will record whether the leaders who built the most powerful technology ever created used their position to coordinate its governance—or whether they continued racing while warning about the destination.

The mechanism exists. The philosophical alignment exists. The public support exists. What remains is the decision to act.